Adam Smith thought his Theory of Moral Sentiments to be more important than The Wealth of Nations for which he is much better known. An intended work on government was never completed. The Theory of Moral Sentiments places him firmly in the Scottish Enlightenment with its belief in the possibility of improvements in society, but he departs from most other writers, including Hutcheson, who believed in an overarching ‘reason’ which could be used to judge actions and create proposals and from Hume that actions should be evaluated according to their utility, or usefulness.

Smith argued that the rules of society and the moral sentiments that guided them arose from the social interactions between people. Although people follow their self-interest, they have a natural sympathy with other people and like to see them happy. In looking at the emotions of others they make judgements based on the causes of these emotions and this relates to what they have seen before and so, although Smith thought that there was a natural feeling of right and wrong innate in people, customs developed that set the rules for society.

The tenor of Smith’s analysis is that the judgements of ordinary people are sound, they should be free to make them and this will generally allow them to live in harmony with others and prevent them from doing harm. If they do good that was all to the better but government should not force this on them. Smith was sceptical of intellectual systems based on reason that proposed grand schemes for the improvement of society.

Smith thought that Government had a role to play in preventing people from doing harm, but should leave business to business people who understood it, although business people should also be kept away from government, a theme he elaborated in The Wealth of Nations.

He followed Locke in arguing that rich people took little more for their own consumption than poor people, but used their wealth to employ others and so the overall produce created by their control of produce from natural resources was actually shared out. Whereas Locke saw this as part of a divine plan for the benefit of society, Smith used the ambiguous phrase ‘the invisible hand’, possibly with a touch of irony. The rest of The Theory of Moral Sentiments involved a detailed discussion of how the types of sympathy worked in different circumstances.

In contrast with The Theory of Moral Sentiment, An Inquiry into the Wealth of Nations is a large rambling work, full of examples, and charting the various historical phases of human economic activity, occasionally arguing in different directions. Nevertheless it marks a major development of economic thought.

Smith’s main argument was that wealth did not consist of a country’s store of gold and silver, but the annual stream of goods which it had, though he was only concerned with physical goods and not services. A growth in wealth depends on the division of labour (Smith’s famous example was the pin factory, where breaking down the process of making a pin into various repetitive tasks, instead of one person making the pin, vastly increased production) but wealth also depended on capital accumulation.

Increased capital, following from the division of labour, could be exchanged for other goods or invested in machinery, which could be used to increase production further. The extent to which division of labour could progress depended on the size of the market and so better trade and transport with other countries increased the size of the market and thus wealth.

The market system was self-balancing, as long as there was free trade and no Government protection or subsidy of industries. If products were scarce, the price would go up and industrialists would invest capital, and if the price fell because of over-production, they would switch capital into more productive areas. Smith also discussed, without really solving, the problem of determining whether the value of a good was based on the amount of labour needed to produce it or the price it fetched in the market.

Smith had a strongly democratic view in believing that all humans were similar in intellect and it was their occupation that determined their wealth. He was concerned that the monotony of work created by the division of labour would be dehumanising and felt that Government should counteract this by providing other outlets for people.

He noted that when labourers combined to increase wages, the full force of powerful opinion was against them but when employers combined to reduce wages there was no reaction. He feared that the influence of employers on government would reduce competition and, in his famous phrase, “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices”. He clearly saw a role for the State but this was a period when government consisted of a web of patronage and favouritism and writers of different views wanted to reduce its role.

Adam Smith was writing at a time of relative political stability and prosperity for Britain, especially in Scotland, where he lectured at the University of Glasgow. What has been called the Industrial Revolution was in its early stages; canals and the new toll roads were improving transport, new processes in iron production, textiles and chemicals were in use, and trade with North America was expanding through the port of Glasgow. Smith spotted the ability of James Watt and was his patron when the local iron manufacturers’ association resented the competitive effect of his inventions.

Scotland was one of the most educated parts of Europe and Smith found the University of Glasgow much in advance of Oxford, which he also attended. The Scottish Enlightenment of the later 18th century encompassed a number of thinkers such as Frances Hutcheson, who was Smith’s lecturer, and David Hume. These thinkers had a strong belief in the ability of human society, and the individuals within it, to improve and in the power of reason as a means of analysis.

Smith was also reacting against current Mercantilist ideas which dominated the economic theories of European countries. The doctrine held that wealth was to be found in the stock of gold and silver that a country owned and so nations, to become more prosperous, should increase exports and imports by protectionist policies to achieve a favourable balance of payments and so increase its gold and silver. Smith travelled to France as tutor to the Duke of Buccleuch and was impressed by Quesnay, the leader of the Physiocrat School which criticised mercantilism but saw wealth as deriving from the land and agriculture.

|

|

|

Smith rests in a line of political philosophers who contributed to the development of liberal thought. Its main tenets, belief in individual self-determination, strict limits to government intervention and the possibility of continuous improvement in a society dominated British political thought from the mid 19th century until the shock of the First World War and the economic dislocation that followed it.

Smith also contributed to the suspicion of grand schemes that have been a view of British Conservatism. The ideas of social interaction and the importance of customs are similar to the social psychology approach and the concept of norms in modern sociology and mark a departure from the 18th-century faith in the application of pure reason.

Smith developed some of the key maxims of economic theory. With Ricardo, he created classical economics which, with the addition of utility theory by Bentham and Mill, made the system of neo-classical economics, still the dominant paradigm, possible.

By linking supply and demand with investment, Smith laid the foundations of resource allocation theory and the idea that the market allocates resources efficiently. The benefits of the division of labour and how this relates to the market is the basis of the theory of the firm.

The labour theory of value was taken up by Ricardo and Marx and Marx also drew on Smith’s stage of economic development. Probably too much has been made of the phrase ‘the invisible hand’ but Smith removed the religious basis that Locke had given to ideas of wealth and the market allocating resources for the ultimate benefit of all and provided clearer economic arguments.

Belief in the market’s ability to solve economic problems was dominant in British Government economic practice, until challenged by Keynes at the level of the aggregate economy in the 1930s, and was revived again in the 1970s.

Ricardo, with his theory of comparative advantage, elaborated Smith’s theory of trade and their arguments were gradually taken up within politics to justify free trade. Huskisson, as President of the Board of Trade in the late 1820s, started to dismantle protection, and the Liberal MPs, Cobden and Bright, regularly used Smith’s arguments against agricultural protection with success in 1846.

Free trade and the prevention of monopoly became central planks of the Liberal Party and helped it to dominate politics from the 1850s to the 1880s and to defeat Conservative demands for protection in the elections of 1910 and 1923. Protection was only introduced by the Conservative-dominated National Government in 1932 and dismantled again after 1945.

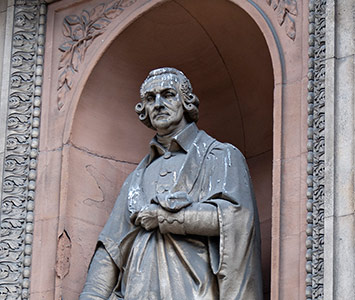

Although his views on government are ambiguous, Adam Smith is the only political philosopher to have a modern think tank named after him and the Adam Smith Institute promotes ideas of freedom, the market and reducing big government.

The two works are his Theory of Moral Sentiments which is a work of philosophy, or even social psychology, and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.