In 1337 King Edward III had begun the Hundred Years War by claiming that he was the rightful heir to the French throne. When his great grandson Henry V was crowned at Westminster on 9th April 1413, this claim continued with Henry also giving himself the title King of France.

Henry V was the son of a usurper. His father Henry Bolingbroke had seized the throne from King Richard II and had himself crowned Henry IV. During his reign he had faced rebellion and rival claims to the throne. Henry V felt that his own rule was insecure. He wanted to prove to his subjects that he was the rightful king and was determined to reclaim the English lands in France.

France was in the midst of a civil war. The French king Charles VI suffered from periods of mental illness and the leading noble families, the Burgundians and the Orleanists (Armagnacs) were fighting each other for power. The French were worried that Henry V might take advantage of the political unrest and exploit France’s weakened state.

Envoys were sent to the French King to negotiate the terms of a marriage between his daughter, Catherine of Valois, and Henry V. As well as wanting a substantial marriage dowry, Henry also demanded that the English lands in France be returned.

In November 1414 Parliament agreed to Henry’s request for a tax to raise funds for a possible war with France, to reclaim what the Chancellor, Bishop Beaufort of Winchester called “…the inheritance and right of his crown outside the realm which for a long time has been withheld and wrongfully kept…”. Parliament granted the tax on the condition that Henry continued to try for a peaceful solution and enter into further negotiations with the French. By this time peace had been restored in France. Although Henry reduced his demands, the French rejected his offer. Henry could now justify his invasion of France.

On 29th April 1415 indentures for the army were drawn up. These were contracts between the Crown and the leading nobles who would each raise an agreed upon number of men at arms and archers. They were known as indentures as the contracts would be written out in duplicate and then cut in half in a jagged line. Each party retained a copy. As well as stipulating the rates of pay, which varied according to a person’s status, the contracts also set out how any money made from the ransom of prisoners and spoils of war would be shared.

Although Parliament had granted him taxes to pay for the war with France, Henry still did not have enough money to finance the campaign. A large number of loans were given by the Church, towns, cities and wealthy individuals, including Richard (Dick) Whittington. Henry also had to use his own crown jewels and plate to pay his army.

Henry also had the problem of finding enough ships to transport his army to France. Ships were hired from Zealand and Holland and merchant ships were requisitioned. Henry’s army probably numbered about 12 000 men, but this figure does not include the great number of non-combatants that travelled with the army. There were also thousands of horses, weapons, armaments, equipment and provisions to be transported across the Channel.

At the end of July Henry’s army was mustering in the countryside around Southampton while Henry himself was at Portchester Castle. On 31st July Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March went to the king and informed him that there was a plot to kill him. The conspirators believed that Edmund Mortimer should be king as he had a stronger claim to the throne than Henry. Three of the conspirators in the Southampton Plot, Sir Thomas Grey, Henry, Lord Scrope and Richard, Earl of Cambridge were executed a few days later.

On August 7th Henry left Portchester Castle and sailed down the coast to his ship the Trinity Royal. At 3pm on Sunday 11th August the fleet, which could have numbered as many as 1500 ships, sailed for France.

Harfleur was a walled town at the mouth of the River Seine. From here the French launched naval attacks on the English coast and on merchant ships. Capturing Harfleur would help protect England and serve as a useful base from which to launch further attacks against France.

On the afternoon of 13th August Henry’s fleet landed a few miles from Harfleur. They began to disembark the following day. Henry issued a series of ordinances to control the behaviour of his army in France. These included not robbing churches or attacking priests, unless they were armed and no man was to ‘cry havoc’, havoc being the military order to loot and pillage.

Henry’s forces laid siege to Harfleur. Henry asked them to surrender and open the gates, but the French refused. Guns and catapults bombarded the walls and the town inside causing considerable damage, but the defenders did not give up and repaired the damage during the night. Attempts to mine under the walls were unsuccessful. The garrison inside consisted of only a few hundred men, but Harfleur was well defended.

Eventually on 18th September a ceasefire was declared. It was agreed that messengers would be sent to ask for help but if the French King did not send reinforcements by 22nd September, the town would surrender. When no relief arrived, the town opened the gates.

The siege had gone on much longer than anticipated. The hot weather, the flooded fields and the unsanitary conditions of the army camp had led to an outbreak of dysentery. Hundreds had died, more than would be killed fighting during the campaign. Those too ill to continue were placed on ships to be invalided back to England.

A garrison of 1200 men under the command of Thomas Beaufort, Earl of Dorset was left to defend Harfleur, along with all of the heavy artillery. Henry V and the remainder of his army set off for the English held territory of Calais, from where Henry intended to sail back to England.

Henry left Harfleur between 6th and 9th October. The army marched overland, following the coast northwards towards Calais. His men had been ordered to bring enough provisions for eight days. Henry wanted to reach Calais as quickly as possible. Winter was coming and some of these men were still suffering with dysentery. There were also reports of a French army gathering at Rouen.

On 11th October they had reached Arques. In return for not burning the town and the surrounding fields the inhabitants of Arques supplied Henry’s army with provisions and allowed them free passage. Similar negotiations took place at Eu the following day.

Henry had hoped to cross the River Somme at Blanche-Taque, the place where Edward III had crossed before the Battle of Crecy in 1346. Word was received that the crossing was unpassable and French forces were gathering on the opposite bank. The English army moved inland to find another crossing further upstream, shadowed by the French.

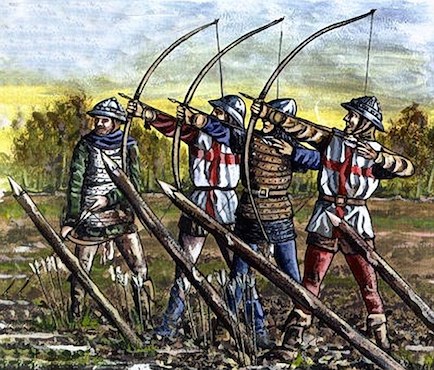

The English army finally crossed the River Somme on 19th October near Peronne. Learning that the French had a large number of cavalry ready to attack his archers, Henry ordered them to prepare six foot long sharpened wooden stakes.

On 24th October Henry’s army crossed the River Ternoise at Blangy. Climbing the hill to the north they came upon the French army massing in large numbers about half a mile away. Believing they would attack, Henry drew up his army into battle formation. The French army withdrew to a nearby field and took up a defensive position between Tramecourt and Agincourt (Azincourt). Henry repositioned his army to face the French, staying in formation until certain that no attack would be made that day. Both sides made camp for the night. Henry ordered his men to camp in silence to guard against any surprise French attack during the night.

Before dawn, sunrise was about 6.40am, the armies began preparing for battle.

Exact figures are not known, but the English were certainly outnumbered by the French. The most important difference however, was in the composition of the two armies. The English army had more archers than men at arms. The Gesta Henrici Quinti, an English eyewitness account, puts the numbers at 5000 archers and 900 men at arms. Although there were French archers and crossbowmen present they played very little part in the battle. Most of the French attacking force was made up of heavily armoured men at arms.

Due to the small size of the English army, it is probable that the battles (divisions) were drawn up into one line. All the men at arms would fight on foot. Henry commanded the main battle in the centre. The Duke of York was in command of the vanguard on the right of the line and Lord Camoys the rearguard on the left. Both men were experienced soldiers. The majority of the archers were on the wings, with smaller groups amongst the men at arms. These were under the control of Sir Thomas Erpingham, one of Henry’s household knights. The baggage train was ordered to be brought up to the rear.

The French formed themselves up into three lines. The vanguard at the front was much larger than the main battle as many of the leading French nobles insisted on being in the front line. Mounted men at arms were placed on the wings.

The two sides remained drawn up in position. Henry had a very strong defensive position, but waiting only made the English army weaker. The men were tired and they were short of food. They had marched over 400km and many were suffering with illness and disease. The French showed no sign of attacking and more men were on their way. Henry could wait no longer and decided to attack first.

Sometime after 10am Henry gave the order to ‘advance banners’ and the English army moved their line forward. The French had been taken by surprise. Their cavalry, disorganised and with fewer men than expected, charged at the archers. The French men at arms in the vanguard advanced on foot. The archers opened up with an arrowstorm. Volley after volley of rapid arrow fire from English and Welsh longbows rained down on the French soldiers.

The French cavalry charge failed. They had to ride straight at the archers as the woodland on either side of the English line prevented the cavalry from outflanking them. Unable to get through the rows of sharpened stakes that protected the archers, the cavalry retreated under a hail of arrows back through the lines of the French men at arms, breaking up the vanguard.

It had rained the night before leaving the freshly ploughed ground wet and muddy. Clad in heavy plate armour the French men at arms struggled through the thick mud. By the time they reached the English lines they were exhausted. Fierce hand to hand fighting began. The arrowstorm and the narrowing of the battlefield had caused the French men at arms to bunch together. They were so closely packed that they had little space to fight effectively and many were pushed over by those advancing behind them or fell over men lying on the ground. Those that fell to the ground were unable to get up and were crushed by the weight of men falling on top of them. Some of the archers joined in the fighting, finishing off the men at arms lying helpless on the ground, stabbing them through the weak points in their armour. Across the battlefield there were piles of French dead and wounded.

As the French vanguard broke up the English men at arms rushed forward to attack the French main battle. With their attack in disarray the French withdrew. The fighting had lasted around three hours. Henry believed that he had won the battle and the English began searching the battlefield for their wounded and for French prisoners that could be held to ransom.

During the battle the English baggage train at the rear had been attacked and plundered. There were still a large number of the French rearguard left and at some point it was thought that the French were re-grouping to launch another attack. Henry ordered all but the most high value prisoners to be killed, fearing that they might turn against them and join in the attack. The French retreated and left the battlefield.

The French nobility had been decimated. Thousands had been killed or captured. The English losses were much lower, with maybe only a few hundred casualties.

Henry returned to England to a hero’s welcome, with a spectacular victory procession through London on the 23 November. Henry’s victory at Agincourt had proved to his subjects that he was the rightful king of England, believing that God had granted him the victory over the French.

King Henry V made further military conquests in France. Under the terms of the Treaty of Troyes in May 1420, Henry and his heirs would inherit the French Crown on the death of King Charles VI.

The Battle of Agincourt – 25th October 1415