The United Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy, governed by ministers of the crown in the name of the sovereign, who acts as both head of the state and of the government.

The three branches of government in the United Kingdom are made up of the legislature, the executive and the judiciary. The legislature is made up of members of the Houses of Parliament, the House of Commons the legislative chamber and the House of Lords the revising chamber.

The executive is made up of Her Majesty’s government, members of the cabinet and other ministers, government departments and local authorities.

The judiciary operate within the law courts and pronounce on the law both written and unwritten, interprets statutes and is responsible for the enforcement of the law; the judiciary is independent of both the legislature and the executive.

Parliament is the law making authority and can legislate is whole or in part for the whole of the United Kingdom. The main functions of Parliament are to make laws and to enable the Government of the day to raise taxes and to scrutinise the Government in its policy making and its administration. Parliament also ensures that Government expenditure; international agreements and treaties are all brought presented to Parliament prior to ratification.

Parliamentary procedure is based on convention and precedent, partly formulated in the standing orders of both Houses of Parliament, and each House has the right to control its own internal proceedings and to commit for contempt.

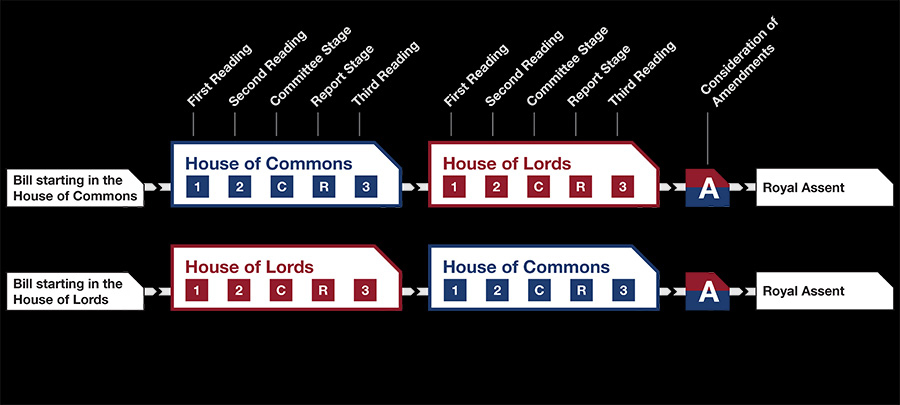

The system of debate in the two houses is similar; when a motion has been moved, the Speaker proposes the question as the subject of a debate. Members speak from wherever they have been sitting. Questions are decided by a vote on a simple majority. Draft legislation is introduced, in either house, as a Bill. Bills can be introduced by a government minister or a private member, but in practice the majority of bills which become law are introduced by the Government. To become law, a bill must be passed by each house and then sent to the sovereign for the Royal Assent, after which it becomes an Act of Parliament. Proceedings of both houses are public.

The minutes which are referred to as votes and proceedings in the House of Commons and the House of Lords and the speeches which are referred to as The Official Report of Parliamentary Debates, Hansard are published daily. Parliamentary proceedings are also televised live and recorded for transmission on radio and television.

Proposed legislation which politicians would like to become law is called a ‘Bill’. There are a number of stages that the Bill needs to go through before it becomes a law.

This is the stage that merely constitutes an order to have the Bill printed.

This is a debate on the principles of the bill.

This is the detailed examination of a Bill, clause by clause. In most cases this takes place in a Public Bill Committee, or the whole House of Commons may act as a committee. Public Bill committees may take evidence before embarking on detailed scrutiny of the bill. Very rarely, a Bill may be examined by a Select Committee.

This is a detailed review of the Bill as amended during the committee stage. This will take place in the House of the Commons.

This allows final debate to be made on a Bill. Public Bills go through the same stages in the House of Lords, but with important differences: the committee stage is taken in committee of the whole House or in a Grand Committee, in which any Peer may participate. There are no time limits, and no selection or amendments can be made at third reading.

A Bill may start in either the House of Commons or the House of Lords, and has to pass through both houses to become law. Both Houses have to agree the final text of a Bill, so that amendments made by the Second House are then considered in the originating house, and if not agreed, sent back or themselves amended, until agreement is reached.

The Royal Assent is signified by letters patent to such bills and measures as have passed through both Houses of Parliament (or bills which have been passed under the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949). The Monarch has not given Royal Assent in person since 1854.

On occasion, for instance in the prorogation of Parliament, Royal Assent may be pronounced to the new Houses by Lords Commissioners. More usually Royal Assent is notified to the House of Commons and the House of Lords sitting separately in accordance with the Royal Assent Act 1967.

The power to withhold assent resides with the Monarch but has not been exercised in the United Kingdom since 1707.

The Conservative Government introduced, in 2015, a significant change to the process of agreeing legislation. Devolution for Scotland and Wales revived what has been called the West Lothian Question, first raised by Tam Dalyell, the MP for that constituency, in the 1970s. English MPs no longer voted on issues that affected only Scotland or Wales or Northern Ireland as these had been largely devolved but Scottish and Welsh and Northern Ireland MPs voted on issues that affected only England at Westminster. One solution to this problem would be equivalent devolution to an English Parliament which would choose an English Government but there has not been enough political support for this.

During the Scottish Referendum campaign, party leaders agreed further substantial devolution to Scotland and, as a result, David Cameron committed the Conservative Party to ‘English Votes for English Laws’ and put this into the Conservative 2015 general election manifesto. This was carried out by the new Conservative Government in 2015, by a change in the House of Commons Standing Orders rather than by legislation, and basically provided that, while legislation still needed a majority of all MPs to pass the Commons, a majority of English MPs could veto the provisions of a Bill that the Speaker has ruled as relating only to England. The first Bill went through the new process in January 2016.

Although EVEL is an answer to the West Lothian Question, several problems arise:-

The new system works in the following way:-

This is a Bill to authorise the issue of money to maintain government services. The Bill is dealt with without debate.

Money Bills (Bills designed to raise money through taxes or spend public money) start in the Commons and must receive Royal Assent no later than a month after being introduced in the Lords, even if the Lords has not passed them. The Lords cannot amend Money Bills.

A bill that is promoted by a body or an individual to give powers additional to, or in conflict with, the general law, and to which a special procedure applies to enable people affected to object.

This is a public bill promoted by a Member of Parliament who is not a member of the Government.

Diagram by BRITOLOGY Ltd

The first reading is the first stage of a Bill’s passage through the House of Lords. Usually a formality, it takes place without debate. The first reading of a Bill can take place at any time in a parliamentary session.

The long title (indicating the content of the Bill) is read out by the Member of the Lords in charge of the Bill.

Once formally introduced, the Bill is printed. The next stage is second reading – the first opportunity for Members of the Lords to debate the main principles and purpose of the Bill.

The first reading is the first stage of a Bill’s passage through the House of Commons. Usually a formality, it takes place without debate. First reading of a Bill can take place at any time in a parliamentary session.

The short title of the Bill is read out and is followed by an order for the Bill to be printed.

The Bill is published as a House of Commons paper for the first time. The next stage is second reading, the first opportunity for MPs to debate the general principles and themes of the Bill.